Our Community Pathways of Support and Referral for Learners in Distress will assist all NorQuesters with reflecting prior to acting, recognizing, responding to and referring learners in distress as well as personally replenishing. All of us can play a part in understanding distress, and looking for meaningful ways to support learners.

Download the full model

Make a priority, confidential referral here

Reflect

Considering questions, or using self-reflective practices, can help individuals to identify unhelpful implicit bias or stigma they may uphold related to mental health.

Examples

-

Am I self-aware and understand how my own emotions and actions can impact the learner in distress? Do I need to calm myself or find support for myself prior to engaging with the learner?

-

Am I able to self-regulate and think before I act, in order to assess the situation and ease any potential tension?

-

Can I display empathy for the learner, withhold judgement, and simply acknowledge the stress or distress they are feeling?

-

Am I able to actively listen and use other appropriate social skills to help the learner feel at ease?

-

Do I have the emotional capacity to engage with the learner in the moment? Do I require assistance from others, or can the situation wait until I have the capacity to assist?

Of course, the urgency of the situation may require one to act immediately, even if not as prepared as desired.

Reflect on any implicit biases or stigma

-

When possible, it is also helpful to reflect on any implicit biases or stigma that may act as barriers to assisting learners in distress. Do you consider it to be someone else’s role – other than your own - to support learners in distress?

-

Is it the learner’s own fault that they are now in distress and need assistance?

-

Are you scared or frightened because of the way in which a learner is reacting to stress?

-

Are you viewing the situation from your own lens or perspective, rather than being empathetic?

-

Do you perceive the learner is depressed and lacks willpower to succeed?

Why Reflect?

Implicit biases or stigma can be difficult to overcome. Reflect and recognize one’s own implicit biases or mindsets related to the stigma of mental health as a key first step. Consider (AAFP, 2022):

- Introspection – exploring prejudice via self-analysis and taking implicit association tests

- Mindfulness – reducing stress and increasing mindfulness through activities such as focused breathing

- Perspective-taking - considering the point of view of the other person

- Learning to slow down – pausing and reflecting to reduce knee-jerk reactions

- Individuation – evaluating people based on personal characteristics and shared interests, instead of group characteristics

- Checking your messaging – using statements that are welcoming and that embrace differences

- Institutionalizing fairness – supporting diversity and inclusion

No one is being asked to act as a counsellor, social worker or mental health professional. However, understanding how and when to refer learners in what circumstances helps to support and encourage learners.

We can learn through reflection.

Reflecting upon our own implicit biases can help us to understand that sometimes what seems to be anger may in fact be emotions associated with systemic racism, trauma and/or oppression. There is a need to consider the impacts of historical trauma and how prevalent trauma is among post-secondary learners in general. Individuals from the BIPOC community are particularly susceptible to trauma. It’s also important to note that individuals with disabilities, 2SLGBTQIA+ community, and other marginalized people may also experience higher rates of trauma (Cantiller, 2021). When reflecting, consider if an individual might be responding from a place of trauma, fear, a situation of the unknown, or uncertainty.

Taking time to breathe, listen actively, and be empathetic are key to supporting learners.

Recognize

Learners are busy and resilient humans! They manage school, home, family, work, and other responsibilities and commitments. As part of everyday living, working and studying, learners may experience stress – that is normal as everyone does! However, when it negatively impacts daily abilities to cope, it can become unhealthy (APA, 2021).

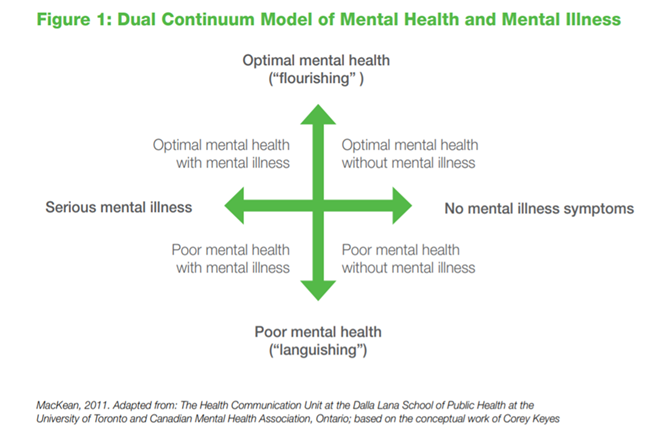

The Dual Continuum Model of Mental Health and Mental Illness, Figure 1, MacKean, 2011 as adapted from Keyes, 2002, in CACUSS & CMHA, 2013) recognizes that an individual’s mental health and mental illness may occur on a continuum moving from poor mental health (languishing) to optimal mental health (flourishing), and that stress, coping strategies, and support all impact mental health.

Figure 1 MacKean, 2011 as adapted by Keyes, 2002

Figure 1 MacKean, 2011 as adapted by Keyes, 2002

Look for indicators of distress

Notice any potential differences or changes in how the learner is presenting (Armstrong et al., n.d.). Consider whether there are pressures of systemic oppression or racism present.

Is the learner telling you there is a problem?

What might distress feel, look, or sound like for a NQ learner?

-

Your anxiety is severe in class today, you think you just had a panic attack. You are scared and not sure how to cope if it happens again.

-

Your roommate just informed you that you can no longer live at their house. You have nowhere to stay tonight or any other night.

-

You just saw an act of violence, can’t stop crying, and are seeing the event replay over in your mind.

-

News that impacts your family who live far away impedes your ability to concentrate on your studies, and you miss classes and assignments.

-

I am caring for my family members while working two part-time jobs and going to school.

Why be proactive?

When a learner is in distress, the cognitive abilities that affect memory and information processing are impacted, mood and mindset are affected, and unnecessary attrition and burnout can be avoided (Harbin, 2015).

Being proactive in addressing learner distress can help to moderate levels of personal stress. This allows faculty and others in positions of support and mentorship to empathize with learners, especially in culturally diverse environments. This can help to decrease compassion fatigue and burnout rates among helping individuals (Harbin, 2015).

Potential indicators of distress

While distress looks different for all learners, there are some general indicators of distress to look for (Note that the following are taken from Burke et al., 2020):

Emotional and cognitive

- Feels very sad or is withdrawn for more than two weeks (can include regular crying, feeling fatigued, and unmotivated)

- Acknowledges experiencing stress, anxiety, and panic attacks

- Exhibits a variety of negative emotions, irrational behavior, lack of judgment, or irritability

Addictive-like & risk-taking behavior

- Problematic internet use

- Excessive use of social media (e.g., Facebook, Instagram) and/or smartphone

- Excessive drinking or use of drugs

- Uncontrolled or secretive gambling

- Extreme risk-taking behaviors

Communication

- Odd behavior and speech patterns

- Impaired speech or garbled and disjointed thoughts

- Bizarre behavior, speech, writing, or thinking

- Engages in angry or hostile outbursts, yelling, or aggressive comments

Social

- Isolation and withdrawal

- Relationship distress

- Friends/peers may report something

- Rejection

- Physical self-harm (i.e., cutting, wearing long sleeves on a blistering hot day)

- Poor personal hygiene

- Appearing lethargic

- Visible weight loss/weight gain

- Excessive or depleted sleep, insomnia

- Shakiness, tremors, fidgeting or pacing

- Disorganized speech, recognizable confusion

- Inability to make eye contact, where previously they did

- Attends class smelling of alcohol or other substances

Faculty-learner relationship

- Dynamics

- Neediness and dependency

- Lack of boundaries

- Excessive disclosure and/or problem-solving about personal issues and crises

- Unreasonable requests

- Excessive meeting requests

- Difficulty ending meetings

- Learners showing up often, spending much of their spare time visiting during office hours or at other times

Academic

- Decreased concentration, motivation, and

- interest

- Procrastination and poorly-prepared work

- Several missed assignments, exams, or appointments

- Infrequent class attendance

- Falling asleep in class

- Extreme disorganization or erratic performance

- Written or creative expression consisting of unusual violence, morbidity, social isolation, despair, or confusion, or focus on suicide or death

- Continual seeking of special provisions (extensions on assignments or deadlines, requesting extra credit or make-up exams)

- Patterns of perfectionism: e.g., can’t accept themselves if they do not get a very high grade/score

- Overblown or disproportionate response to grades or other evaluations

Respond

Assess the situation and use the guidelines in REFER to guide your conversations and actions. Where appropriate, start a conversation with the learner. An initial conversation or inquiry about a learner’s well-being can have a significant impact, often prompting them to access timely help or make the changes necessary to ensure their academic situation isn’t jeopardized (University of Saskatchewan, n.d.).

Here are some suggestions (note that some of the below materials have been borrowed from University of Saskatchewan, n.d.):

Actions

"I've noticed you leaving class/seeming upset lately. I'm concerned about you. How are things going?"

-

Talk to the learner in a quiet space. Help to create a safe and calming environment. If a conversation in a private space would seem helpful, seek the learner’s consent first.

-

Give the learner your complete attention. Listen without judgment and let them talk without interruption.

-

Acknowledge the learner’s thoughts and feelings with compassion and empathy. “I hear what you are saying, and I am sorry you are experiencing this”.

-

Try using an “I” statement to start a conversation to express your concern. For example, “I’ve noticed that you haven’t handed in the last two assignments and have missed a lot of classes lately, and I’m concerned.” Be specific and direct, describe the behaviours that are concerning and ask how the learner is doing. For example, ”I noticed that you were tearful (not depressed) in the group discussion today. I just wanted to check in and see if you’re okay”. Or, “I noticed your grades have dropped. That can happen when courses get more challenging, but sometimes it happens when learners have other things going on that affects their studies. Is that happening to you?”

-

Repeat their statements to clarify and ensure that you understand what the issues are. For example, you could say, “I want to be sure I understand what you are saying. Is this what you meant?”

-

Let them know you are concerned and want to help them find the right resources. “I am concerned, and I think I can assist you by helping you to find some resources”.

-

Acknowledge common stressors and experiences. Learners often have the “I’m the only one” experience. While it is important for a learner to have their experience respected, there are times it can be helpful to know that other learners have similar experiences. For example, many first-year learners question whether they have what it takes to succeed at college, but think they are the only ones who don’t have it all worked out. “How are you finding things? I have seen many first-year learners struggle with balancing assignments”.

-

Acknowledge stressors and experiences that may be oppressive in nature. Consider cultural and diverse situations and be empathetic.

-

Consider any flexibility you may offer as it pertains to academic matters. Set clear expectations.

-

Consider any flexibility you may offer as it pertains to academic matters. Set clear expectations.

-

Use a strengths-based approach: “I am concerned and was wondering if you had support at home, in your community, or elsewhere, and if I can assist you to connect with someone?”

Is the situation distressing or an emergency?

For distressing or emergency situations, act and (D) REFER at once.

For non-urgent situations, referrals are still helpful, although immediate help is not always necessary. Sometimes a follow-up conversation can assist as well.

If a learner has included something troubling in an assignment and you are concerned about the learner for that reason, invite the learner to discuss the matter. You might also consider contacting your Chair and/or the Centre for Growth & Harmony if you are unsure how to approach the situation.

You do not have to be an expert in mental health, but actively listen and be aware of potential indicators of distress so you can refer learners to campus supports and community resources when needed.

Refer

Where appropriate, recognize and explain your own knowledge limitations. Inform learners that NorQuest has a lot of resources and support for learners, and that community resources may also be helpful. Help to normalize the support and let the learner know that asking for assistance is okay.

See Community Pathways of Support and Referral for Learner in Distress Overview: Assess the situation and determine whether the situation is an emergency (immediate threat to self or others), distress/distressing situation (distressing situation requiring attention but not immediately life- threatening), or non-crisis (experiencing distress and may still benefit from further resources and support).

"It sounds like things are stressful right now. I'm glad we could talk about it. There are some great supports on campus. Here is their information..."

Offer to follow up with the learner and see if there are any academic issues arising where further assistance may be necessary.

“I am going to check in with you in a day and see how things are going.”

It is important to note that even if you have the learner’s best interest in mind, a learner may not want to access further services or support.

Unless the situation is an emergency, leave the door open for a conversation at another time:

“You can come back to talk to me or access these services whenever you need them. Don’t hesitate to ask”.

Or, “I am going to check in with you in a week and see how things are”.

Helping to reduce any stigma about referrals is important:

“I understand it can be difficult to seek assistance.” or “You seem reluctant to use these services. Are there questions that you have about how these services can assist, or do you have any concerns?”

Referral process

Emergency situations

Emergency situations should be dealt with immediately and not through the referral process. If the learner is threatening suicide, harm to self or others, or acting in a very bizarre or out-of-touch manner:

-

If the learner is on campus, immediately contact the Centre for Growth & Harmony or Security, and stay with the learner until support arrives (see On-Campus Emergency Contacts).

-

If the learner is off-campus or the Centre for Growth & Harmony is closed, call 911. Follow up later with the Centre for Growth & Harmony.

If your own safety is not at risk, say "I am very concerned for you. I'm going to make a call to get some help."

Distressing situations

In highly distressing situations requiring attention (help is needed, but no immediate threat of harm to self or others is identified), make a priority, confidential referral for campus resources here.

"It sounds like things are really stressful right now. There are some great supports on campus. Let's contact them to get some help now."

Please note that responses for referrals will be received within 2 business days. If on-campus at the downtown centre, drop-in crisis counselling is also available through the Centre for Growth & Harmony during regular business hours.

Non-Urgent

No referral is needed to the Centre for Growth & Harmony or other Student Services, but when in doubt, do refer.

What can I expect if I refer?

Learner choice and confidentiality

Unless there are reasonable and probable grounds to believe that a child is in need of intervention - in which case there is a duty to report - or in certain life-threatening emergency situations, the learner has a choice whether to seek additional help or resources. It is the learner’s decision, and you can aid the learner by letting them know that if they do not wish to obtain support at this time, you can be approached again. “You can come back to talk to me or access these services whenever you need them. Don’t hesitate to ask”.

Accepting the learner’s choice and their values is important; if you identify resources and options for the learner, in a trusting relationship, there is a greater likelihood the learner will return for assistance when they feel it would be most beneficial. You can also seek assistance from the Centre for Growth & Harmony on how to best assist the learner.

(Note that some of the following information is adapted from University of Prince Edward Island, n.d.)

Following up

Once you have made a referral, you can follow up with the learner directly by asking how they are doing. This communicates your ongoing concern and care for the learner and lets them know that you can continue to be a valuable resource. Keep in mind that change is a process, and therefore improvement may be slow and variable. Be mindful of the learner’s choice.

Just as your own privacy would be protected should you be referred to another resource, so, too, must we respect the privacy and confidentiality of any learner situation. This means that the Centre for Growth & Harmony, or other internal resources, cannot provide you with information about the learner, including whether the learner has attended an appointment or any specifics of the situation. However, general questions about making referrals and you sharing information regarding the specifics of a situation are appropriate. Let the learner know that you do have a duty to report if children are involved.

If you submit an online referral at norquest.ca/learnerindistress, you will receive a response from the Center for Growth & Harmony within 2 business days, so that you know that your concern is being addressed. Please be aware that it is important to respect a learner’s privacy: you may only share information on a need-to-know basis to ensure the learner’s safety. If the learner does not wish to obtain support at this time, respect their choice and let them know you are there for them.

In situations where a learner is a danger to themselves or others, support is needed immediately. Treat it as an emergency.

Declining assistance

Sometimes a learner will decline assistance. Taking time to educate the learner about free, confidential, professional services is sometimes helpful. Identifying what the hesitation is about, or myths and misunderstandings about counselling, may be helpful as well. If the learner does not want assistance, you have offered resources and made them further aware of help.

The “buddy system” may also be helpful for some learners; you could offer to facilitate an online or in-person meeting with the Centre for Growth & Harmony (walk the learner over or facilitate an e-introduction). You can provide the learner with the wellness@norquest.ca email address so they can make their own connection, too.

Overall, provide options for the learner to decide the most comfortable way they would like to obtain the help (virtually, by telephone or in person). Remember that you can follow up a day or two later with the learner to see how they are doing. Don’t feel obligated to take on the responsibility to support the learner on your own. Make the learner aware of the resources, offer assistance, and remember that it is the learner’s choice to seek assistance in most cases.

Stigma and culture

Sometimes a learner is concerned with the stigma surrounding mental health or may have different world views than your own about health and well-being. Respecting cultural differences is important. For more information, you may wish to see Mental Health Across Cultures.

Sharing information about counselling may be helpful as well. If the learner does not want assistance, you have offered resources and made them further aware of help.

Don’t feel obligated to take on the responsibility to support the learner on your own. Make the learner aware of the resources, offer assistance, and remember that it is the learner’s choice to seek assistance in most cases.

Referrals and resources

While emergency referrals and referrals for learners in distress are explained, there are a number of other options for referrals that may be helpful.

NorQuest Resources

Another option is Togetherall which is a free, safe online community where Canadians can support each other anonymously to improve mental health and well-being.

Replenish

Thank you for working as a community to support NorQuest learners! If you need to debrief a situation with a learner, please don’t hesitate to contact the Centre for Growth & Harmony. Your supervisor can also be a good support.

The college also has more formal support for employees through the Employee Assistance Program (EAP).

Recognizing that you might need assistance replenishing, NorQuesters have free access to Lifeworks (User ID: norquest; Password: eap) where you can find tips and resources for energizing, as well as other supports.

Acknowledging that working with learners in distress can be stressful itself, please think about ways that would be helpful for you to replenish. Thinking about boundary-setting is one way that may help one replenish. While those in higher education often strive to build connections with learners, setting boundaries to ensure a healthy relationship is also important.

Tips (Eidinger, 2020; Higgins, 2018)

-

Be clear about spaces. Learners need permission to be in your space. If they are ‘granted permission’ to connect via social media or of-campus activities, mixed messages may result.

-

Communicate your office hours and general availability. Schedule email times, giving “cool-down” time after grading assignments (do not email for 24 hours or so).

-

Consider how much time you spend talking about your personal life as compared to their success.

-

Consider healthy limits on where you go with learners, and activities that you take part in.

-

Know that you can’t always meet the needs of every learner. Communicate that you are there to support them and aid them. Refer and connect, and supply resources up front.

-

Establish clear expectations – communications, conduct, etc.

-

Use your network for support and ideas.

References

-

American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) (2022). Eight tactics to identify and reduce your implicit biases.

-

American Psychological Association (APA). (2021, April). Stress relief is within reach. American Psychological Association.

-

Armstrong, G., Daoust, M., Ycha, G., Seinen, A., Shedletzky, F., Gillies, G., Johnston, B. & Warwick, L. (n.d.). Capacity to connect: supporting students’ mental health and wellness. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

-

Burke, M.G., Laves, K., Sauerheber, J.D., & Hughey, A.W. (Eds.). (2020). Helping college students in distress: A faculty guide (1st ed.). Routledge.

-

Canadian Association of College & University Student Services and Canadian Mental Health Association (CACUSS & CMHA). (2013). Post-Secondary Student Mental Health: Guide to a Systemic Approach. Vancouver, BC: Author.

-

Cantiller, D. (2021). Trauma, healing and learning in the Canadian postsecondary institution.

-

Eidinger, A. (2020). Tips for maintaining emotional boundaries when teaching. Careers Café: University Affairs.

-

Harbin, B. (2015). Keeping Stress from Evolving into Distress: A Guide on Managing Student Stress through Course Design. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching.

-

Higgins, J (2018). What you’re forgetting when you set boundaries with students.

-

Kulinska, K. E. (2021). Supporting Faculty in Responding to Distressed Students. The Organizational Improvement Plan at Western University, 208. Retrieved from https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/oip/208

-

University of Prince Edward Island (UPEI) (n.d.). A faculty and staff guide to helping students in distress.

-

University of Saskatchewan (U of S) (n.d.) Recognizing signs of distress.